Rule Breaker

I love to learn, to do new things and make new things happen. To find quality, and create it where it is lacking. The pursuit of quality is more than a mission statement. It demands constant focus and rigour.

As a venture philanthropist, I am always asking “How well are we doing?”, “Did that meet its target?” and “How could our funding have more impact?”, and I think those questions probably shaped my whole life.

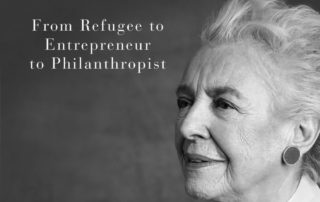

My life, my story, is one of meeting adversities head-on, and turning them into opportunities. I arrived in Britain as a five-year-old Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied Europe, clutching nothing but a doll and my elder sister’s hand. I retired a multimillionaire atop an 8,500-strong IT empire of my own making, and since then I have set about ridding myself of my fortune: and revel in the good it is achieving.

I loved maths with a passion from a very young age. But I wasn’t supposed to study maths – I was a girl! And needed to change schools twice in order to be taught it. Tuition was eventually provided in a boy’s school – where I experienced the daily gauntlet of leering catcalls. Sexism and stereotypes were rife.

There were very few prospects for women in work when I started work at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in London, because all expectations then were about home and family responsibilities. I met my husband, Derek while working, and when we married in 1959, I did what was expected of women working in the same organisation as their husbands: I resigned my job.

But then I did something much less predictable – and not for the last time in my life. I launched my own business creating and selling software. We began on the dining room table with what would now be a hundred pounds, financed by my own labour and a second mortgage on our home. My mission was to help women get jobs and to avoid misogyny in the workplace. Almost all the early employees were women, and many, like me, worked flexible hours, spending time at home with young children. It was a crusade for women, to be able to work in a family-friendly way, and be respected for their capabilities. I believed, and proved, that women could be mothers and have a career without compromising performance.

There’s still much to do when it comes to equality between the genders in the workplace. However, I like to think about how far we’ve come. Women before us had so many barriers to overcome and thanks to the suffragettes, we enjoy — and sometimes take for granted — the opportunities that women have today.

It’s hard to believe, but in the early ’60s a woman couldn’t open a checking account without her husband’s permission. Around the world, women couldn’t go to work without the fear of sexual harassment on a regular basis. There were barriers, legal and social, preventing ambitious women from finding their place outside the home.

I couldn’t accept those restraints, and resisted and fought against them. When my business development letters, sent from the double feminine Stephanie Shirley, were binned without even being opened, I changed my name to Steve, so as to get through the door before anyone realised that “he” was a “she”.

But I wasn’t the only one. My generation of women fought the battles for the right to work and for equal pay. Today, women expect men to fight alongside, for still we fight.

I never set out to make millions. My friends thought I did not have the temperament to survive in the carnivorous environment of business – any business. But I came to enjoy its freedom and intellectual challenge. At its peak in 2000, the company was worth almost $3bn. By the time it was acquired, I’d made 70 of my staff into millionaires.

Because I was a refugee and so many people helped me, I became a philanthropist to help others. Because I was a refugee, I learnt to welcome change, otherwise I wouldn’t have survived. I have donated a great deal to not for profit causes: over $30m of my own money to IT (my professional discipline) and more than double that to autism (my late son’s condition). My approach is in accordance with my business mission: pioneering – never more of the same, no matter how worthy – and strategic.

Because I was a refugee and so many people helped me, I became a philanthropist to help others. Because I was a refugee, I learnt to welcome change, otherwise I wouldn’t have survived. I have donated a great deal to not for profit causes: over $30m of my own money to IT (my professional discipline) and more than double that to autism (my late son’s condition). My approach is in accordance with my business mission: pioneering – never more of the same, no matter how worthy – and strategic.

Because philanthropy is personal, it will always be chaotic. I select the issues that interest me and the problems I seek to address with my funding. There are millions of problems to be solved and individuals have the right, in most countries, to select which causes to support. Yes, of course, I can join with others; but this would be unlikely on a global scale.

Disruption and innovation, rule-breaking, challenging the status quo are the seeds of change. We are lucky to live in a time and place where a lot of walls have been broken down. I got to own a modern business, work with big clients and sign my real name in business correspondence. That makes me very grateful.

Dame Stephanie Shirley CH

[email protected]

https://www.steveshirley.com/

Twitter: @DameStephanie_

FaceBook: https://www.facebook.com/DameStephanie/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/damestephanie_

https://www.let-it-go.co.uk/

TEDtalk 2015 (2.2 million views): Why do ambitious women have flat heads?

Rule Breaker

I love to learn, to do new things and make new things happen. To find quality, and create it where it is lacking. The pursuit of quality is more than a mission statement. It demands constant focus and rigour.

As a venture philanthropist, I am always asking “How well are we doing?”, “Did that meet its target?” and “How could our funding have more impact?”, and I think those questions probably shaped my whole life.

My life, my story, is one of meeting adversities head-on, and turning them into opportunities. I arrived in Britain as a five-year-old Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied Europe, clutching nothing but a doll and my elder sister’s hand. I retired a multimillionaire atop an 8,500-strong IT empire of my own making, and since then I have set about ridding myself of my fortune: and revel in the good it is achieving.

I loved maths with a passion from a very young age. But I wasn’t supposed to study maths – I was a girl! And needed to change schools twice in order to be taught it. Tuition was eventually provided in a boy’s school – where I experienced the daily gauntlet of leering catcalls. Sexism and stereotypes were rife.

There were very few prospects for women in work when I started work at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in London, because all expectations then were about home and family responsibilities. I met my husband, Derek while working, and when we married in 1959, I did what was expected of women working in the same organisation as their husbands: I resigned my job.

But then I did something much less predictable – and not for the last time in my life. I launched my own business creating and selling software. We began on the dining room table with what would now be a hundred pounds, financed by my own labour and a second mortgage on our home. My mission was to help women get jobs and to avoid misogyny in the workplace. Almost all the early employees were women, and many, like me, worked flexible hours, spending time at home with young children. It was a crusade for women, to be able to work in a family-friendly way, and be respected for their capabilities. I believed, and proved, that women could be mothers and have a career without compromising performance.

There’s still much to do when it comes to equality between the genders in the workplace. However, I like to think about how far we’ve come. Women before us had so many barriers to overcome and thanks to the suffragettes, we enjoy — and sometimes take for granted — the opportunities that women have today.

It’s hard to believe, but in the early ’60s a woman couldn’t open a checking account without her husband’s permission. Around the world, women couldn’t go to work without the fear of sexual harassment on a regular basis. There were barriers, legal and social, preventing ambitious women from finding their place outside the home.

I couldn’t accept those restraints, and resisted and fought against them. When my business development letters, sent from the double feminine Stephanie Shirley, were binned without even being opened, I changed my name to Steve, so as to get through the door before anyone realised that “he” was a “she”.

But I wasn’t the only one. My generation of women fought the battles for the right to work and for equal pay. Today, women expect men to fight alongside, for still we fight.

I never set out to make millions. My friends thought I did not have the temperament to survive in the carnivorous environment of business – any business. But I came to enjoy its freedom and intellectual challenge. At its peak in 2000, the company was worth almost $3bn. By the time it was acquired, I’d made 70 of my staff into millionaires.

Because I was a refugee and so many people helped me, I became a philanthropist to help others. Because I was a refugee, I learnt to welcome change, otherwise I wouldn’t have survived. I have donated a great deal to not for profit causes: over $30m of my own money to IT (my professional discipline) and more than double that to autism (my late son’s condition). My approach is in accordance with my business mission: pioneering – never more of the same, no matter how worthy – and strategic.

Because I was a refugee and so many people helped me, I became a philanthropist to help others. Because I was a refugee, I learnt to welcome change, otherwise I wouldn’t have survived. I have donated a great deal to not for profit causes: over $30m of my own money to IT (my professional discipline) and more than double that to autism (my late son’s condition). My approach is in accordance with my business mission: pioneering – never more of the same, no matter how worthy – and strategic.

Because philanthropy is personal, it will always be chaotic. I select the issues that interest me and the problems I seek to address with my funding. There are millions of problems to be solved and individuals have the right, in most countries, to select which causes to support. Yes, of course, I can join with others; but this would be unlikely on a global scale.

Disruption and innovation, rule-breaking, challenging the status quo are the seeds of change. We are lucky to live in a time and place where a lot of walls have been broken down. I got to own a modern business, work with big clients and sign my real name in business correspondence. That makes me very grateful.

Dame Stephanie Shirley CH

[email protected]

https://www.steveshirley.com/

Twitter: @DameStephanie_

FaceBook: https://www.facebook.com/DameStephanie/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/damestephanie_

https://www.let-it-go.co.uk/

TEDtalk 2015 (2.2 million views): Why do ambitious women have flat heads?